Prevention is better than treatment, and so knowing how to stay healthy by keeping the immune system resilient is always relevant. While talk of boosting immunity may have some of us reaching for the Vitamin C or Echinacea pills, a whole new field of research indicates that it is a happy belly we should be aiming for instead: healthy and balanced gut bacteria can reduce both the incidence and severity of chest infections, colds and flu1. These bacterial colonies that call our guts (and other body areas) home constitute the microbiome. The microbiome is the focus of a lot of current research, and an out-of-whack microbiome is being linked to conditions as diverse as:

• Obesity

• Autism

• Depression

• Anxiety

• Mood disorders

• Diabetes

• Asthma

• Allergies

• Emphysema

• Multiple Sclerosis

• Inflammatory Bowel

• Colorectal Cancer

• Rheumatoid Arthritis

• Leaky Gut

• Metabolic Syndrome

An increasing number of trials are revealing that adjusting and rebalancing the microbiome can have powerful results in the treatment of these conditions.

So what IS the microbiome exactly?

The microbiome refers to the sum total of microbes (microorganisms such as bacteria or fungi) that live in, or on, various parts of our bodies. The vast majority of these guys are found in the large intestine, and have a combined weight of up to 1.5kg. If this seems like a lot, consider that this 1.5kg contains over 100 trillion bacteria! This number means that in a healthy human, microbial cells can outnumber “human” cells by a factor of 10 to 1: expressed in another way, over 90% of the cells that make up “me” are bacteria and other microbes! Mindboggling stuff, which might make you wonder “who actually am I?”

Making things even more interesting, the microbiome is highly individual (like a bacterial fingerprint!) and changes over time, responding to environmental factors, stress and diet. This finding sits well with the Chinese Medicine perspective that an individual’s state of health fluctuates over time and in relation to environment, emotions and lifestyle.

But these bacterial buddies of ours aren’t getting a free ride: the microbiome has many important roles in the mind-body, including the metabolism and assimilation of nutrients, immune regulation, brain development and behaviour2, so changes in bacterial population, diversity and relative colony sizes have a direct impact on health. Research into this area is relatively new, but already we are learning that the microbiome is closely linked to immune function. Imbalances of certain bacteria can lead to compromised immunity, and can also contribute to autoimmune conditions such as Crohn’s (in which the immune system is upregulated to attack the body itself). Some fascinating studies have revealed that while the human genes associated with Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) differ between European and East Asian populations, a deficiency of the same bacteria was implicated in both populations3: this hints at the vast potential of microbiome regulation in treating a broad range of currently unaddressed chronic and degenerative diseases.

Chinese Medicine knows that good digestion is at the root of good health

Though the microbiome is only recently being “discovered” by modern science, Chinese Medicine has recognized the fundamental importance of healthy digestion for thousands of years. In Chinese Medicine symbology, digestive function is allocated to the Spleen-Stomach and is represented by the element Earth, highlighting the grounding role of healthy digestion in optimal health. Indeed, the oldest surviving Chinese Medicine classical text* assigns digestion / Earth a central position amongst all the other organs and body systems, acknowledging the essential foundation that it provides.

In recognition of the pivotal role of digestion, Chinese Medicine places great focus on a healthy and individually appropriate diet. The father of modern Western Medicine, Hippocrates held a similar view, suggesting we “let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”. This sentiment has unfortunately been all but drowned out in modern medicine – much to our detriment, as the choices that we make several times daily have a direct impact on our health and wellbeing. Indeed researchers suggest that our ancestral microbiome is facing an extinction crisis as a result of the modern, refined diet4.

Are all bacteria “good”? Aren’t there any “baddies” in there?

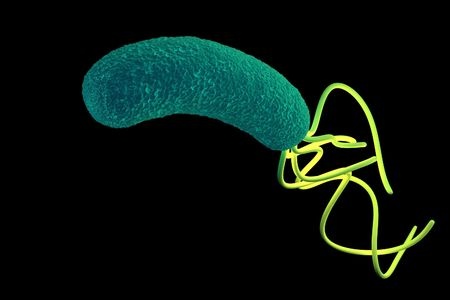

As in Chinese Medicine, good health lies in dynamic balance and things are not simplistically black-and-white: some bacteria can cause disease when their numbers are either excessive OR too low. For example, the bacterium Helicobacter pylori has been linked to gastritis and peptic ulcers, however an absence (or insufficient numbers) of that same bacterium are also implicated in asthma, Crohn’s and the modern spate of allergic disorders1, 5, 6. One of the suggested factors contributing to an insufficiency of H. pylori is the increased use of antibiotics in recent decades5.

Helicobacter pylori: friend… and foe.

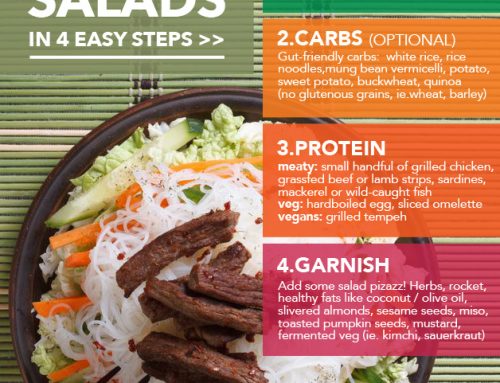

Optimal bacterial balance starts with gut-loving foods and great digestion. Some of our ancestral microbiota rely on the carbohydrates sourced from fermentable fibres (these are present in whole plant foods, such as root vegetables, leafy greens, onions, avocados, nuts and herbs) and when there isn’t enough of this fermentable fibre for them to munch on, they will start to eat away at the protective mucus layer of the gut. Such “cannibalism” eventually erodes the gut lining, allowing microbial waste (endotoxins) to enter the blood stream. Tellingly, endotoxin levels in the blood increase after eating sugary, greasy and processed foods4. These endotoxins spur the immune system into action, triggering the systemic inflammation that is linked to so many modern diseases. Therefore, it is imperative to ensure that we have enough of these fermentable fibres – also called “prebiotics” – in our diet.

Weak digestion is also a culprit in causing bacterial imbalance. Impaired digestion of foods further up the digestive tract (see inset) means that they arrive at the lower digestive tract (the large intestine, home of much of the microbiome) insufficiently metabolised to be broken down effectively. Here, they can be fermented to act as fodder to prompt the overgrowth of certain bacterial strains (while also producing gases that lead to symptoms such as pain, bloating, constipation and/or diarrhea). This situation of microbial imbalance is called dysbiosis.

SOME FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO INSUFFICIENT DIGESTION

Rushed meals and insufficient chewing: chewing initiates digestion by breaking food down into smaller particles, while our saliva contains important digestive enzymes that further support this process.

Stress: stress activates the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS), which primes the body for fight-or-flight by diverting blood circulation to the muscles, heart and lungs; unfortunately in doing so, blood circulation is diverted away from digestive organs, inhibiting their function (read more about this here).

Weak stomach acid: too many fluids at or around meal times can dilute stomach acid, which is essential to good digestion.

Inappropriate food choices: sugary foods7 (this includes fruit!) are easily fermentable and can fuel proliferation of unfavourable numbers of bacteria; certain fibre (ie. from wholegrains like brown rice, wheat bran, wholegrain wheat & rye) can be difficult to digest, causing issues further down the tract (interestingly, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) sufferers are also advised to avoid fructose (fruit sugar) and insoluble fibre).

What else can cause dysbiosis?

As mentioned earlier, the refined modern diet, with its highly processed foods, chemical additives and decreased diversity is not beneficial for happy bacterial balance. The concurrent modern trend of increased hygiene has been a mixed blessing, as it has also reduced the diversity of our microbiome8. Current research is looking into how popular antimicrobial handwashes and other cleaners affect the microbiome, with findings suggesting that these agents negatively impact our gut bacteria – and can increase the risk of infection9. The further decimation of bacteria with widespread antibiotic use is increasingly implicated in the subsequent development of certain inflammatory conditions, suggesting that wiping out certain bacteria can render the immune system prone to disregulation. Further research suggests that a similar mechanism can predispose an individual to the food allergies that are ever-increasing in modern society. 5,7

Another interesting factor that can affect microbiome health and diversity is the mode of delivery at birth. Vaginal delivery squeezes the baby and coats the newborn with a liberal dose of the mother’s own bacteria, providing a microbiome “starter kit”. A caesarian delivery circumvents this process, and some research suggests that these babies may be more at risk of subsequently developing asthma, Type 1 diabetes, eczema, allergies and celiac disease, and are more likely to be hospitalized for gastroenteritis.10,11 A novel intervention is now being trialled, where babies delivered by caesarian section are “seeded” with bacteria by swabbing with a gauze that has been placed in the mother’s vagina an hour before delivery. This swabbing results in a newborn microbiome that is closer to that of a baby born vaginally.

So, how can you support your bacterial buddies?

• Avoid drinking large amounts of fluids with, or around meals

(this can excessively dilute stomach acid, which is integral to managing bacterial overgrowth).

• Eat foods that optimise digestion to prevent fermentation further down the digestive tract:

think well-cooked, warm meals – Asian cuisines are a great inspiration!

• Limit fruits and sugars (which can be fermented if incompletely digested).

• Support your digestion by taking time to eat your meals in a relaxed environment.

• Include fermented probiotic foods, especially fermented vegetables (these contain Lactobacillus plantarum and brevis, which may directly enhance the function of our gut lining8).

• If you eat meat, choose antibiotic-free, ethically raised products; farmed meats contain both antibiotics and herbicides from animal feed.

• Use antibiotics wisely (this is in line with recent recommendations by a range of medical peak bodies; see the Choose Wisely initiative).

• Meditate: studies have shown that stress negatively affects bacterial balance, leading to dysbiosis (which further negatively affects moods and can create a vicious cycle).

• Limit processed foods and chemical additives.

• Go easy on the antibacterial hand sanitisers – a bit of bacterial diversity is a good thing (this doesn’t mean you don’t have to wash your hands, but just ease off on these antibacterial cleansers).

• While insufficient fibre makes for hungry bacteria, at the other end of the spectrum, too much fibre can also cause disease: in Chinese Medicine, we look to gut & stool health to provide feedback on the current state of affairs.

• Stop smoking, limit alcohol intake and get a good night’s sleep regularly – all factors shown to have a positive impact on gut flora.

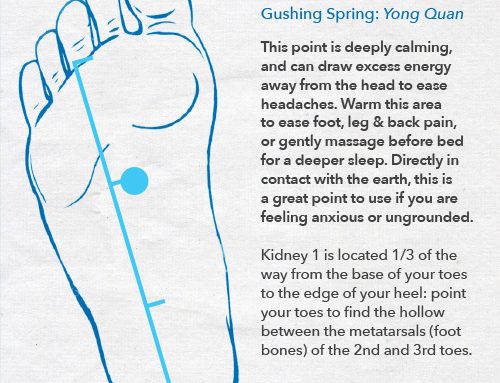

Acupuncture and Chinese Herbal Medicine can optimise the microbiome

Chinese Medicine has been shown to therapeutically affect the body along various pathways (i.e. the nervous and endocrine systems12, 13), so it is unsurprising to discover that acupuncture and Chinese Herbal Medicine can exert a range of positive effects on the microbiome. A study into the effects of acupuncture on gut bacteria found that using acupuncture points indicated for digestion had a regulating effect on intestinal flora. After 20 acupuncture treatments, numbers of the beneficial bacteria Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium increased, while Clostridium perfingens and Bacteroides (which may be linked to obesity when their numbers are elevated) decreased – and the Body Mass Index (BMI) of obese study participants dropped from 27.76 to 25.27.14

Chinese Herbal Medicine has also been shown to have a therapeutic effect on the microbiome. Herbal formulas such as Si Jun Zi Tang (a popular digestive tonic) and Shi Quan Da Bu Tang (a formula with broad applications, from fatigue to various immune disorders) have been shown to beneficially regulate gut bacteria, and in turn, affect gene expression.15

Let’s look after each other!

As we continue to discover just how much the microbiome contributes to our state of health, it is becoming more apparent just how important it is to cultivate happy belly bacteria. And the great news is that it is never too late to start: the microbiome can start to adjust within days of switching to a diet and lifestyle that supports our little friends. So let’s thank them for all the work they do to keep us healthy, with a little microbiome TLC!

* The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine, or Huang Di Nei Jing, dating to around 200BCE.

REFERENCE & FURTHER READING

- Racaniello, V. (2011). Gut microbes influence defense against influenza (6.9.2011).

Retrieved from http://www.virology.ws/2011/09/06/gut-microbes-influence-defense-against-influenza/

- Hollister, E. B. et al. (2015). Structure and function of the healthy pre-adolescent pediatric gut microbiome. Microbiome, 3(36).

- Velasquez-Manoff, M. (2015). Gut Microbiome: The Peacekeepers. Nature, Vol. 518, Issue s7540, pS3-S11.

- Velasquez-Manoff, M. (2015). How the Western Diet Has Derailed Our Evolution. Nautilus, Issue 030 (2). Retrieved from http://nautil.us/issue/30/identity/how-the-western-diet-has-derailed-our-evolution

- Blaser, M. J., Chen, Y. & Reibman, J. (2008). Does Helicobacter pylori protect against asthma and allergy? Gut, Vol. 57, Issue 5, pp.561-567

- Jin, X., Chen, Y. P., Chen, S. H. & Xiang, Z. (2013). Association between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Ulcerative Colitis – A Case Control Study from China. International Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 10 (11). Pp.1479-1484

- The Microbiome and Disease. Retrieved from http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/microbiome/disease/

- Pollan, M. (2013). Some of My Best Friends Are Germs. New York Times, 15.5.2103) Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/19/magazine/say-hello-to-the-100-trillion-bacteria-that-make-up-your-microbiome.html

- Mole, B. (2016). Mounting data suggest antibacterial soaps do more harm than good. Ars, (10.4.2016). Retrieved from http://arstechnica.com/science/2016/04/mounting-data-suggest-antibacterial-soaps-do-more-harm-than-good/

- Molloy, A. (2015). Mothers facing C-sections look to vaginal ‘seeding’ to boost their babies’ health. The Guardian, (18.8.2015) Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/aug/17/vaginal-seeding-c-section-babies-microbiome

- Neu, J. & Rushing, J. (2011). Cesarean versus Vaginal Delivery: Long term infant outcomes and the Hygiene Hypothesis. Clinics in Perinatology, Vol. 38 (2), pp. 321-331

- Li, Q. Q., Shi, G. X., Xu, Q., Wang, J., Liu, C. Z. & Wang, L. P. (2013). Acupuncture Effect and Central Autonomic Regulation. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Vol. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3677642/

- Villas-Boas, J. D., Dias, D. P. M., Trigo, P. I., Almeida, N. A., Almeida, F. Q. & Medeiros, M. A. (2015). Acupuncture Affects Autonomic and Endocrine but Not Behavioural Responses Induced by Startle in Horses. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Vol. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4568046/

- Xu, Z. T., Li, R. F.., Zhu, C. L. & Li, M. Y. (2013). Effect of acupuncture treatment for weight loss on gut flora in patients with simple obesity. Acupuncture in Medicine, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 116-117

- Li, H. K., Zhou, M. M., Zhao, A. H. & Jia, W. (2009). Traditional Chinese Medicine: Balancing the Gut Ecosystem. Phytotherapy Research, Vol. 23, pp. 1332-1335.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/gut-bacteria-brain-cognit_n_7644484.html?

Thank you for sharing such wise advice. The older I get the more I realize how important it is to listen to my body. The information presented here reinforces my conviction to lake care of my temple and listen more intently.

Great article.